Unknown fear: Madison residents are increasingly alarmed by PFAS levels in local waterways

Cap Times | 11 Dec 2019 | Steven Elbow

- Film on PFAS in theaters, started early December Dark Waters Trailer

- Documentary on PFAS DuPont vs. the World: Chemical Giant Cover Up

“Lance Green has been collecting water samples from Starkweather Creek for years. As a volunteer for the state Department of Natural Resources, he records observations of temperature, water clarity, dissolved oxygen each month. Much of that volunteer work involves actually getting into the water.

“I’ve been wading in that water in my swimsuit for years doing the monitoring,” said the retired DNR environmental specialist.

Those days are over. He just bought some chest-high waders.

“I’m taking precautions,” he said.

Green is co-director of Friends of Starkweather Creek, an advocacy group for a body of water popular with east Madison paddlers, anglers and other urban water enthusiasts. It’s also a toxic mess, listed by the state as an “impaired” waterway because of the PCBs, heavy metals, DDT byproducts and other chemicals that have fouled the water for years.

Recently, Green has become more concerned with a different pollutant: per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances, better known as PFAS. The substances have been around for decades, but improved testing methods have found them in a growing list of water supplies. The Environmental Working Group estimates that 110 million Americans — more than a third of the population — may be exposed to PFAS in their drinking water.

PFAS turned up indetectable levelsin 10 of Madison’s 19 municipal wells, as well as four seasonal wells, prompting the closing last summer of Well 15 on the city’s east side, a 750-foot-deep reservoir near the Air National Guard’s Truax Field.

As an expanding body of science links the chemicals to serious health problems, and more contamination comes to light, the public is getting uneasy.

Last week, Public Health Madison and Dane County installed about 30 PFAS warning signs along Starkweather Creek telling people to avoid swallowing water and the foam that sometimes forms on it, and to wash themselves and their pets if they become exposed. In a mixed message, the signs also say the water is safe to touch.

Nationally, communities most affected by the chemicals are located near manufacturing facilities and military bases, where PFAS-containing firefighting foam had been used for training since the 1960s. Truax appears to be the primary source of Madison’s PFAS problem.

But Starkweather Creek is its poster child.

The creek is a magnet for kids from the low-income and middle-class neighborhoods through which it runs. And it’s a stormwater repository from known and suspected sources of PFAS: Truax Field, two adjacent pits once used for firefighting training, and the former Burke sewage treatment plant, once operated by the Guard and where significant concentrations of PFAS were detected last spring.

The PFAS levels in Starkweather are alarming for Maria Powell, executive director of the Midwest Environmental Justice Organization, particularly because some people depend on the fish they catch from it. [Check out MEJO]

“We don’t have the data yet, but those fish are probably full of PFAS, ” she said. “Because it builds up to really high levels in fish. (The levels) can be thousands of times more than what’s in the water.”

Add to that the stormwater sources from a sewer pipe installation at Reindahl Park, a months-long project that could pump up to 150,000 gallons of PFAS-containing water each day into a storm drain that empties into the creek.

For Green, who organizes canoe and kayak events and enlists kids for creek cleanup activities, it’s no way to treat what he calls an “urban gem.”

“It’s tough because we advocate for the health of the creek and for the enjoyment of the creek,” he said, “and both of those things are now being challenged by this new PFAS threat.”

Concerns extend beyond Madison

Elsewhere in the state, wells have been closed in Rhinelander and La Crosse. High levels of PFAS have been detected at Mitchell International Airport in Milwaukee. They’re in the waterworks in West Bend, the Army Reserve base in Fort McCoy and Volk Field Air National Guard at Camp Douglas.

That could be the tip of the iceberg. In Michigan, a color-coded map of PFAS hotspots looks like lights on a Christmas tree, not because Michigan has more PFAS contamination than other states, but because the state has decided to test for them.

“We have not been systematically looking for them yet, but they are out there,” said Darsi Foss, head of environmental management at the Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources. She is taking a lead role in the state’s efforts on PFAS contamination.

Last summer, the DNR named Madison, which used to own the Truax property, Dane County, the current owner, and the Air National Guard as parties responsible for the presence of PFAS.

But local officials are downplaying the threat.

At a recent meeting of the City Council’s Executive Committee, Mayor Satya Rhodes-Conway pointed to increasing media attention and the recent release of “Dark Waters,” a Hollywood movie about PFAS contamination, and advised alders to prepare for a growing wave of public concern.

“We expect that there’s going to be heightened awareness of the issue in the community and want to make sure that you all have the resources you need to respond to that,” she said.

PFAS, she said, is only one contaminant among many.

In Rhodes-Conway’s view, concern over PFAS is overblown.

“It happens to be the one the community is most concerned about right now,” she said. “But that, I think, doesn’t mean it is the most concerning contaminant in the bigger picture, or the only thing we should be worried about.”

Tell that to Doug Oitzinger and the other 14,000 residents of Marinette and Peshtigo off the northern coast of the bay of Green Bay, where rural small-town charm has given way to angst.

“People are sitting on this poison,” said Oitzinger, a former Marinette mayor who lives a few blocks away from Peshtigo-based Tyco Fire Products, which for decades has been testing PFAS-laden firefighting foam and training people to use it.

It was two years ago that Tyco’s parent company, Johnson Controls, made public test results that began to shed light on what’s now being viewed as an environmental disaster, the extent of which is still unknown, but which is known to be vast.

“This plume is 7 to 10 square miles of contamination in the groundwater, and growing,” said Oitzinger, who organized a local group to demand answers as to why and how the contamination came to be, and what can be done about it.

The plume from the company’s training facility is expanding under homes and seeping into wells, streams and basements. Those who used to drink water they once thought clean now drink from bottles supplied by Tyco. Nobody knows if it’s safe to eat the fish they catch or the deer they harvest.

The contamination in Marinette may have spilled into the countryside. For more than 50 years, the company has pumped PFAS through a Marinette wastewater treatment facility that is not equipped to remove them, so they pass through to the Menominee River. What doesn’t pass through is captured in sludge known to be contaminated, and which for at least 30 years has been spread over thousands of acres of farm fields, possibly contaminating yet-untested fields, the crops that grow on them and the wells below.

Tyco has been testing and training people to use PFAS foam since 1962. Company officials knew of the contamination in 2013, but didn’t tell residents until 2017, keeping them in the dark about the health risk for four years. For some, that meant four years of drinking tap water with up to 27 times federal advisory level of PFAS for safety, and 95 times the level proposed by the state.

Residents are starting to fear a connection between the chemicals and their health.

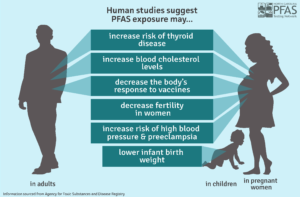

The list of serious illnesses linked to PFAS exposure includes kidney and testicular cancer, thyroid disease, ulcerative colitis, liver disease, high cholesterol, reduced responses to vaccines, low birth weight, birth defects, delayed development, problems with fertility and pregnancy-induced hypertension.

“There seem to be a lot of people in this area that have thyroid problems, who have various forms of cancer,” said Oitzinger, who is thankful to own a home about two blocks from the Peshtigo town border, where he gets city tap water that has registered only low levels of PFAS.

But, he added, “It’s all anecdotal. There’s no study, there’s nothing where we can say this is a clear, direct, irrefutable link between the contamination and the illnesses that they’re suffering.”

`Forever chemicals’

PFAS are a family of man-made chemicals, known as “forever chemicals,” whose indestructible molecular carbon-flourine bonds allow them to exist possibly for centuries in the environment.

DuPont discovered the compounds in 1938, which led to the development of Teflon and later 3M’s waterproof, stain-resistant Scotchgard.

Their unique chemical make-up give them a remarkable resistance to water, oil and heat. PFAS compounds have been used for a mind-boggling array of applications, from industrial machinery to dental floss. They could be in your hairspray, in the wax that allows your skis to glide swiftly over the snow.

Some products insert them directly into your food. They’re the reason microwave popcorn bags don’t burst into flames. They could be in the paper wrapped around your burger and the disposable plates you load with hot dogs and potato salad at a summer barbecue.

And since the 1960s, they have been widely used in firefighting foams that can extinguish a raging jet-fuel inferno in seconds, particularly by the military, which mandates their use. Chemicals from the foam can travel through soil, groundwater and storm sewers. For instance, an application of firefighting foam last summer after a transformer fire at Madison Gas and Electric is the likely cause of elevated PFAS levels at an outlet into Lake Monona under Blount Street, about a third of a mile away.

PFAS exist in a measurable level in nearly every American. They’ve been detected in wildlife species from deer in the Midwest to polar bears in the Arctic.

Once ingested, they churn through the body for years, allowing them to accumulate faster than the body can flush them out, posing a potentially deadly risk for those who live in contamination zones.

In 2015, a landmark 10-year medical study of 70,000 people living near a DuPont facility in the Ohio Valley found a “probable link” between the PFAS variant PFOA and conditions that included kidney and testicular cancer, thyroid disease, high cholesterol and pregnancy-induced hypertension.

In Merrimack, New Hampshire, residents living near Saint-Gobain Performance Plastic — a weatherproof fabric manufacturing facility — didn’t wait for an official study. Instead, in 2017 they formed a clean water group and enlisted a panel of academics to help launch a survey of 213 households.

The survey found more-than-average incidents of developmental, autoimmune and kidney disorders among those under 18, health conditions that included cardiovascular, respiratory, reproductive and liver disorders among those who worked at the plant, and increased cardiovascular and developmental disorders among longtime residents.

The toxicity of PFAS has been confirmed in numerous other studies, in laboratory experiments and in corporate documents dating back decades that were never released to the public until they were unearthed in court proceedings.

The most widely used and studied PFAS types — PFOA (perfluorooctanoic acid), used to make Teflon, and PFOS (perfluorooctanesulfonic acid), used in Scotchgard — are known as eight-chain PFAS for their number of molecular carbon-fluorine bonds. Those were phased out in the U.S. between 2006 and 2015, but manufacturers have come up with a newer generation of PFAS with shorter-chain molecules of six and, more recently, four carbon atoms, which supposedly allow the human body to eliminate them faster and the environment to break them down more readily.

And they’re being churned out at a dizzying rate, as many as 6,000 to date, creating a confusing alphabet soup of compounds with names like PFHxS, PFNA, PFHpA, PFPeA and FOSA. States are starting to regulate some of these in what some are calling a chemical whack-a-mole.

It’s impossible to test soil, water, sludge and living creatures for all of the PFAS compounds because each test has to be tailored specifically to the variant being sought.

The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency has provided little guidance. The agency maintains a 70-parts-per-trillion (ppt) level set in 2016, but it’s only advisory, and only for PFOA and PFOS.

Unwilling to wait for federal leadership, many states, including New York, New Hampshire, Connecticut, Michigan, Vermont and Minnesota have already or plan to set levels far below 70 ppt and have been adding more and more PFAS to their regulatory lists.

Under Vermont’s standards, which sets a cumulative limit of 20 ppt for five varieties of PFAS, Madison’s Well 15, which was closed despite measuring PFAS below proposed state levels, would have been shut down by government fiat.

The Wisconsin DNR is seeking to expand the state’s proposed 20 ppt regulatory level for groundwater to extend to surface water and drinking water. And the agency recently submitted a list of 34 PFAS for review by health officials, to the chagrin of industry groups.

“We have over 4,000 PFAS compounds in the stream of commerce, many of which are considered to be perfectly safe, and in fact have been approved for years by the FDA for contact with food for human consumption in food packaging,” said Scott Manley, vice president for government relations at Wisconsin Manufacturers and Commerce, the state’s largest business lobby.

But scientists who study the compounds say most of them have undergone no scientific scrutiny, and some of those that have pose many of the same health effects as longer-chain PFAS.

“They’re less toxic when you look at certain health effects, but they’re more toxic when you look at other health effects,” said Jamie DeWitt, an environmental toxicologist at East Carolina University who’s been studying the toxicity of PFAS for decades. “They don’t stay in the body as long, but they still stay in the body a long time compared to drugs we would take.”

Going to court

Upon taking office this year, Democratic Gov. Tony Evers declared 2019 the year of clean drinking water and directed state agencies to take an aggressive approach. Foss, the DNR environmental management director, said the agency has referred the Tyco case to the state’s Department of Justice for possible prosecution.

That would add Wisconsin to a growing list of states taking action against companies accused of knowingly or recklessly discharging the chemicals into the environment, including New Hampshire, New York, Ohio and West Virginia. Michigan has announced probable litigation against 3M and other PFAS manufacturers.

Class action and individual claims are piling up as well, and Oitzinger said a law firm has recently been soliciting people living in the Merrimack and Peshtigo contamination zone.

Duane and Janell Goldsmith, a Marinette couple who for years consumed water from a well contaminated with Tyco’s firefighting foam, filed a lawsuit a year ago. According to a complaint filed in Marinette County Court, they and their two children have elevated levels of PFAS in their blood. Duane Goldsmith has a malignant gastrointestinal tumor, and Janell Goldsmith has suffered with pregnancy-induced high blood pressure. One child was born with low birth weight and both suffer developmental delays.

The Goldsmiths withdrew the case from Marinette County in March. Duane Goldsmith referred questions to Napoli Shkolnik, a New York personal injury law firm that is litigating class action lawsuits against firefighting foam makers, including 3M, DuPont and Tyco. An attorney with the firm didn’t respond to a message seeking comment.

New state action

In the past, Oitzinger had been critical of the DNR. The agency, he said, didn’t respond to his questions or his records requests. He pointed out that it was he, not the DNR, who discovered in documents posted in a DNR database that Tyco failed to report PFAS contamination in 2013, keeping residents in the dark for four years that their health was at risk.

“They weren’t leading,” Oitzinger said of the DNR. “They were following, not being tough, not asking questions. They were floundering.”

But with the election of Evers last year and his focus on clean water, he doesn’t feel that way anymore.

“New people took charge,” he said. “I really feel there’s been a sea change.”

Just weeks ago, the state convened the PFAS Action Council, a panel made up of 18 officials from 16 agencies. The council plans to submit an action plan by June 30, 2020. In a move unlikely under Evers’ Republican predecessor, Scott Walker, business was not given a seat at the table.

That bristles WMC’s Manley, who leads a group called the Water Quality Coalition— with members that include the Wisconsin Paper Council, the Midwest Food Products Association and the American Chemistry Council — to lobby on the PFAS issue.

“The council makeup is very government-centric,” he said. “And I think it was unfortunate that there was not an effort to include industry in the discussion, because whatever the council decides to recommend by way of policy recommendations will certainly impact businesses.”

Manley worries that the DNR will require public water utilities to install expensive filtering equipment, with a cost he estimates in the range of $850 million, not including disposal and maintenance costs.

“And those costs, of course, will be borne by everybody who has a water bill, whether you’re a homeowner or a business,” he said.

Manley said he has no problem with the 20 ppt standard for PFOA and PFOS. But included in the proposals for Wisconsin standards is a 2 ppt “preventive action limit,” which would require water utilities, manufacturers, military units and other entities to notify the DNR of trace amounts, which would allow the agency to require mitigation. Manley calls the action limit a de facto standard, which he claims is the “lowest in the world.”

He noted that governments in Canada, Germany and the European Union, which traditionally have more aggressive regulatory approaches, have limits for PFOA and PFOS that are much higher than the U.S. advisory level.

“The question I think needs to be asked of the DNR and DHS is why are they smarter than Canada, or the European Union, or Germany, or other countries that have set standards that are a lot higher than 20 or 2 parts per trillion?” he said.

Battling bureaucracy

For Powell, of the Midwest Environmental Justice Organization, allowing manufacturers to pump thousands of unstudied, unregulated chemicals into the market is a serious concern.

A longtime environmental activist who lives on Madison’s north side, Powell also thinks the city and county need to do far more about mitigating the fallout from PFAS contamination. She has been pushing the city to take a more active role in monitoring PFAS contamination and protecting vulnerable populations and those eating potentially contaminated fish.

She said local officials, particularly the health department, could do more, like issuing a stronger advisory about the fish. The warning signs along Starkweather Creek say fish are being tested, and that the results will be made public, but it doesn’t warn against eating them.

“The numbers from Starkweather Creek, those are really high numbers,” she said, “and I’m really concerned about the fish. That’s where you’re probably going to see some really high numbers, and we should have had that data a long time ago. A couple fishing seasons have gone by since we started asking for this.”

Powell, who holds a Ph.D. in environmental science, has influenced decisions to widen the scope of testing at the city’s wells. She convinced the sewerage district to test groundwater the city planned to pump into storm drains at Reindahl Park. Those tests found PFAS in the groundwater, but not at high enough levels to convince the city or the state to put the skids on the project. And she worked with alders to get the city to cough up $5,000 to test fish in Starkweather Creek. The results might shed light on how much PFAS anglers are consuming, and they could further ramp up local concern.

All her efforts, she said, have met resistance from the local bureaucracy.

“It just shouldn’t be this way,” she said. “It shouldn’t take all this pushing and begging and constant battling.”

She pointed to studies that suggest the current regulations don’t go far enough. One, from the Trump Administration’sAgency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry, proposes dropping standards for eight-chain PFAS to as low as 7 ppt, a level that takes into account the lower body weight of babies and children, and would provide more protection for pregnant women.

Many people living in the Truax neighborhood, she said, are low-income and minority, and they’re likely getting PFAS from their drinking water, from the fish they catch and possibly from the wind blowing from nearby Truax Field.

“We’ve been working with the Truax neighborhood all along,” she said, “and they were getting water from Well 15. There are a lot of babies and small children there, there are a lot of pregnant women, and we’re seeing scientific literature saying these levels are not protective for infants, especially ones being bottle fed with a lot of water.”

Madison and Dane County officials don’t share Powell’s urgency.

A number of locations with a high risk of contamination haven’t been tested, like the Dane County landfill and the former Oscar Mayer site, where PFAS were likely used in machinery and food packaging, and where Rhodes-Conway hopes to build a bus storage and maintenance facility.

And no testing has been done at the Madison Metropolitan Sewerage District, where up to 36 million gallons a year of potentially contaminated sludge is hauled off to outlying agricultural fields. The district recently announced plans to test in the coming year.

Emails obtained by Powell through the state’s open records law indicate that health and water utility officials were not concerned about PFAS levels in Well 15. The decision to close the well in March did not come from the water utility but from former Madison Mayor Paul Soglin, who was facing a reelection fight just as media reports were ramping up on the PFAS issue.

“I’ll be putting out a press release today on the Mayor’s decision to rely on other wells in the Well 15 area until the State Dept of Health Services issues a groundwater standard recommendation for PFAS,” wrote water utility spokeswoman Amy Barrilleaux in a March 4 email to Doug Voegeli, the environmental health director for Public Health Madison and Dane County. “I do want to mention that PHMDC says Well 15 water is safe to drink.”

Emails also show that Voegeli opposed a proposed task force that would be comprised of water utility, sewer and health officials, city and county elected officials, health experts and residents. The task force would have been charged with making recommendations for a comprehensive response to PFAS contamination, keep the public updated on PFAS and provide a forum for public concerns.

“I am not seeing that this is needed,” Voegeli wrote in a Feb. 19 email to the city assistant attorney drafting the proposal for the task force. “However, if this is to go forward, I would suggest that PHMDC is not the lead as the optics of PHMDC leading a task force for an issue that they have publicly stated is NOT an issue does not seem aligned.”

David Ahrens, a member of the City Council and the Water Utility Board until this year, advocated for the task force. He said Voegeli’s opposition was a key factor in the City Council’s decision last month to table the proposal indefinitely.

Public Health, he said, “wanted to control” the public messaging on PFAS and “didn’t want a second opinion on policy.”

In an interview, Voegeli said PFAS regulation is up to the DNR, not local government.

“What’s driving everything right now is the DNR identifying the city, the county and the Air National Guard as responsible parties and laying out what needs to happen at this point in time in regards to that designation,” he said.

While all that gets hashed out, Public Health is taking a minimalist approach.

“What we’re doing right now is just notification requirements that’s required by the DNR,” he said, “and then putting some temporary signs up” along Starkweather Creek.

Meanwhile, storm drains from Truax, its burn pits, the former Burke sewage treatment facility and other potentially contaminated sites continue to flow into Starkweather Creek. And Green is looking toward spring’s canoe and kayaking get-togethers and kids’ clean-up projects with more than a little apprehension.

“I’m not sure what this is going to mean for our activities,” he said.

He describes the reaction among the water enthusiasts in his group as “sadness, disappointment, fear.”

“Kind of an unknown fear,” he said. “We don’t know how much we should be worried about it.”

Steven Elbow joined The Capital Times in 1999 and has covered law enforcement in addition to city, county and state government. He has also worked for the Portage Daily Register and has written for the Isthmus weekly newspaper in Madison.

Original article…

Unknown fear: Madison residents are increasingly alarmed by PFAS levels in local waterways

They knew. They know. They refuse to stop poisoning us.

For decades, 3M was a leading producer of the toxic fluorinated chemicals known as PFAS. As early as the 1950s, 3M’s own studies showed that PFAS chemicals built up in blood, and by the 1960s, 3M’s own animal studies showed the potential for harm. Yet 3M continued to produce PFAS chemicals without notifying its employees of the risks.