Climate & Environmental Impact of F-35s

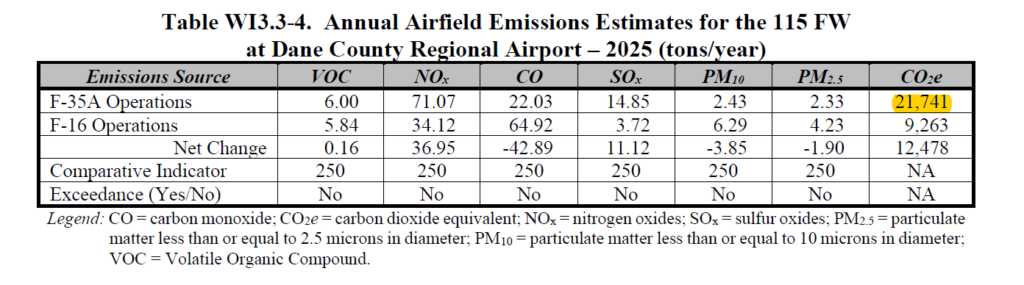

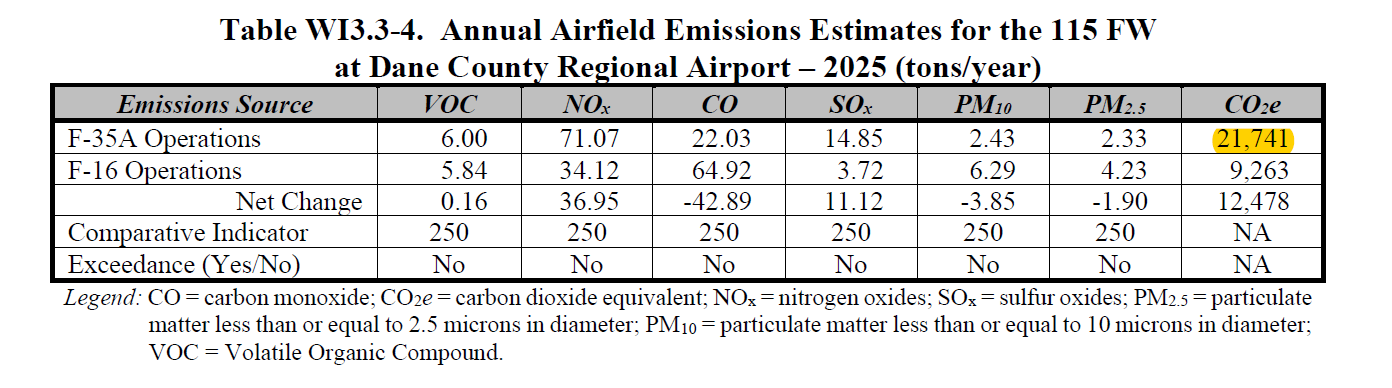

Local greenhouse emissions – Madison

- F35 jet operations – 21,741 tons per year CO2e = 4,248 passenger vehicles onto roads, driving 11,500 miles per year on average.

- The annual airfield CO2e emissions would increase by approximately 12,478 tons or 135 percent. This is equivalent to adding an additional 2,438 passenger vehicles onto roads, driving 11,500 miles per year on average. (This includes additional commuter emissions because of an increase in personnel resulting from the basing of the F-35A).

Each F-35 burns 22 gallons a minute

The F-35 is a climate killer

James Marc Leas | Nov 29, 2021

EXCERPT:

Each F-35 burns 22 gallons of jet fuel per minute, 1,340 gallons an hour. Altogether, the F-35A training flights from the runway in South Burlington Vermont burn between 4.7 and 9.4 million gallons of jet fuel and emit between 100 million and 200 million pounds of CO2 per year. That is the equivalent of the annual emissions of 10,000 to 20,000 passenger cars. Scroll down to the footnote to see details of the calculation.1

U.S. Air Force Environmental Impact Statement

- Draft_F-35A_EIS_Executive_Summary_August_2019

- Final_F-35A_EIS_Vol_I_Feb_2020_Part_2_MadisonWI_BoiseID

Here are the estimated emissions from all the F-35 jets coming to Madison, Wisconsin. This comes from the environmental impact statement prepared by the Air Force.

Emissions in the table above will vary depending on the number and type of flights. These are calculated in Appendix C of the EIS. Appendix C shows that the CO2e emission factor for the JP-8 fuel burned by the F-35 are as follows: 75.2 kg CO2/MMBtu emission factor from Table 2 of Federal GHG Accounting and Reporting Guidance, CEQ (2012), 3.251 lb CO2/lb fuel burned

The F-35 jet fuel consumption rate is 5,600 liters per hour or 1,481 gallons per hour, so it has CO2e emissions of 4,816 pounds per hour, or 2.4 short tons per hour or 2.2 metric tons per hour.

Pentagon Fuel Use, Climate Change, and the Costs of War

Watson Institute, Brown University Environmental Costs | Costs of War (brown.edu)

The Costs of War project conducts and publishes research to facilitate debate about the ongoing consequences of the United States post-9/11 wars in Afghanistan, Iraq and elsewhere; the costs of the U.S. global military footprint; and the domestic effects of U.S. military spending. Created in 2010 and housed at Brown University’s Watson Institute for International and Public Affairs, the Costs of War project builds on the work of over 60 scholars, experts, human rights advocates, and physicians from around the world.

According to Neta C. Crawford, co-director of the Costs of War Project, “all this capacity for and use of military force requires a great deal of energy, most of it in the form of fossil fuel.” As a result, the U.S. Department of Defense is the world’s largest institutional user of petroleum, and therefore the single largest producer of greenhouse gases in the world.

Between 2001 and 2017, the years for which data is available since the beginning of the war on terrorism with the U.S. invasion of Afghanistan, the U.S. military emitted 1.2 billion metric tons of greenhouse gases. More than 400 million metric tons of greenhouse gases are directly due to war-related fuel consumption, with the largest portion of Pentagon fuel consumption being for military jets. As General David Petraeus said in 2011, “Energy is the lifeblood of our warfighting capabilities.”

Militarism and the Climate Crisis

Climate Crisis & Militarism Project – Veterans for Peace

Our Mission: Veterans For Peace Climate Crisis and Militarism Project is part of the world-wide movement to end the climate crisis and promote climate, environmental, racial, and economic justice. Our emphasis focuses on how US militarism, the single largest institutional source of greenhouse gasses on the planet, fuels the climate crisis.

COP26: how the world’s militaries hide their huge carbon emissions

The Conversation | Christian Cachola, November 9, 2021

EXCERPT:

One reason we know so little is due to militaries being one of the last highly polluting industries whose emissions do not need to be reported to the United Nations. The US can take the credit for that. In 1997, its negotiating team won a blanket military exemption under the Kyoto climate accord. Speaking in the Senate the following year, the now special presidential envoy for climate, John Kerry, hailed it as “a terrific job”.

At present, 46 countries and the European Union are obliged to submit yearly reports on their national emissions under the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC). The 2015 Paris Agreement removed Kyoto’s military exemption but left military emissions reporting voluntary.