MEJO’s Maria Powell: Oops! We Poisoned the “Giants Among Us”–Our Lakes

Maria Powell 22 Jan 2021

Madison Environmental Justice Organization

Original Article: Oops! We poisoned the “Giants Among Us”–our lakes

“Today the Wisconsin State Journal reported that the highly toxic “forever chemicals” called PFAS (per-and polyfluoroalkyl substances) were found in all the Yahara Lakes–dubbed “Giants Among Us” in a summer 2018 newspaper series by Steve Verburg.

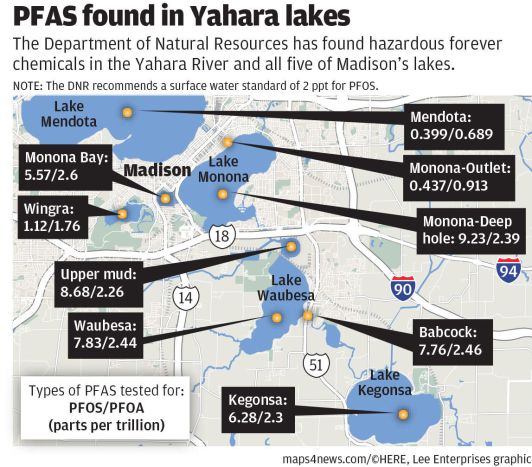

Results for PFOS and PFOA, two of the compounds tested, are depicted below (from WSJ). Full results are here. Highly toxic PFOS can build up in fish to levels thousands of times higher than the levels in water, which is why DNR has proposed a surface water standard of 2 parts-per-trillion (ppt) for PFOS. All of the lakes except Lake Mendota and Lake Wingra exceed this.

Last year, DNR fish testing found up to 180,000 ppt PFOS in Lake Monona fish. Results of DNR’s expanded fish PFAS testing, including fish from all the lakes, will not be available till later this winter or spring.

No surprise–and more testing needed

These PFAS results shouldn’t come as a surprise to anyone. The Dane County Regional Airport (DCRA) and Air National Guard base on Madison’s Northside–the main sources of PFAS–began using fire-fighting foams containing PFAS in the late 1960s/early 1970s (if not earlier). PFAS compounds are highly persistent and non-biodegradable. They never go away.

If more testing was done, especially in Starkweather Creek, Lake Monona and downstream, including sediments–which have not been tested at all other than MEJO’s testing*–even higher levels of PFAS would likely be found. PFAS in lakes and sediments will continuously release PFAS into the water over time.

PFAS compounds have been in the lakes, and slowly building up in sediments, for decades, but nobody measured them before. How long will they be in lake sediments? Probably forever.

Citizens urged testing years ago; government agencies & military resisted, delayed

Madison government agencies and citizens have known for many decades that Starkweather Creek serves as a drainage ditch for sewage, industrial, airport, and military wastes.

As the largest watershed flowing to Lake Monona, the creek has always had a huge influence on the lake’s water quality. In 1970, a Wisconsin State Journal story was subheaded “As goes Starkweather, so goes Monona.”Another story that year described how Madison’s pollution and sewage affects all the downstream lakes.

Agencies should have tested Starkweather Creek, Lake Monona, and downstream lakes for PFAS years before they did–or demanded that responsible parties test. The Truax Air National Guard was identified in 2015 as one of the military bases that likely had used PFAS. Preliminary PFAS testing wasn’t done there till 2017, and very high levels were found in shallow groundwater there, which feeds the creek. All the stormwater at the base also flows into the creek. See more details here.

In spring 2018, MEJO began raising questions about high levels of PFAS at Truax–and demanding fish testing. The mouth of the creek is a very popular shoreline and boat fishing spot.

It took years of difficult advocacy at city, county, and state levels before this testing was finally done by DNR.

One year ago (January 2020), DNR reported that up to 4,190 parts-per-trillion (ppt) of PFOS/PFOA (combined) and over 8,800 ppt total PFAS were found in Starkweather Creek surface water. Up to 180,000 ppt PFOS was found in Lake Monona fish. (Around this time, an Isthmus artist created the Starkweather Creek graphic, left).

In April, 2020, the Dane County Regional Airport reported up to over 18,000 ppt PFOS/PFOA at stormwater outfalls at the airport and Truax military base.

For years MEJO also advocated —with much resistance and foot-dragging from city and county–for PFAS testing at Dane County fire-training areas (burn pits), which were used by the city, county, and military since the 1950s.

One month ago (December 2020) DCRA reported up to over 68,000 ppt PFOS/PFOA in groundwater under the burn pits.

The numbers above are just for two of the most studied and regulated PFAS compounds–though there are thousands out there and about 36 being tested for in our lakes, groundwater, stormwater and fish. The total PFAS levels found in the stormwater at the airport/military base were 32,273 ppt. The total PFAS levels in the groundwater under the burn pits were a stunning 85,247 ppt.

These are among the highest levels–if not the highest–found to date anywhere in the state.

Starkweather creek water–and the groundwater under it– flows into Lake Monona and then downstream into Mud Lake, Lake Waubesa, and Kegonsa. Many PFAS compounds are highly mobile in water. So it’s not at all surprising that all the dowstream lakes, miles away from Truax Field, also had significant levels of PFAS.

Citizens in the dark, no public meetings

In 2019, while pushing for more testing and accountability, we advocated for a Citizens PFAS Task Force, so the public would have some place to go to find out what is going on and have a say in decisions. We organized a lot of public and alder support for it, and all the appropriate city and county committees approved it unanimously. What happened? Read the sad story of its demise here.

The lakes are already contaminated with PCBs, mercury, metals, arsenic and copper sulphate weed-killers, and myriad other toxic chemicals associated with serious health effects. In 1990, a retired city worker, asked to opine about potential harms from building Monona Terrace over the garbage dump under Law Park–who had also applied pesticides on the lakes for decades–asked “Can anything else hurt Lake Monona?” That was 30 years ago.

Now PFAS joins the stew of poisons we know about. There are countless other contaminants that we haven’t yet measured that are nearly 100% likely to be in the lakes and sediments–pharmaceuticals, plastics, many varieties of pesticides–the list is long. Most of them build up in fish.

PFAS are particularly deadly ingredients in the toxic stew. PFAS exposures have been associated with cancer, immune deficiencies, development problems, kidney and liver diseases, elevated cholesterol, obesity, infertility, reduced penis size, and more. Recent studies indicate that PFAS exposures in infancy may reduce the effectiveness of vaccines due to their immune-suppressing effects.

A study just published on December 31, 2020 showed that those with higher levels of one kind of PFAS in their lungs, PFBA, were at higher risk of becoming seriously ill with and dying from COVD19. According to the study, people with more PFBA in their lungs “had higher odds of being hospitalized, winding up in intensive care, and dying than those with lower levels.”

PFBA was found at significant levels in ALL of the lakes. Where did it come from? See more at the end of this post.**

People–especially low income anglers of color– are eating poisons and feeding them to their families. Is anyone warning them?

Many studies show that PFOS can build up to hundreds or thousands of times higher levels in fish than in the water, depending on the fish species. The DNR’s proposed surface water standard for PFOS of < 2 ppt was based on calculations intended to prevent PFOS from building up in fish to levels harmful to human health. All of the lakes other than Lake Mendota and Lake Wingra have levels exceeding this.

Again–some fish in Lake Monona have up to 180,000 ppt (180 ppb) PFOS in them.

The DNR told the State Journal that fish PFAS results for all the lakes will not be available till later in the winter or spring. DNR’s Adrian Stocks “declined to speculate on whether it’s safe to eat fish from those waters, though he said if people are concerned they can follow consumption advice issued last year for fish from Lake Monona.”

Telling people to simply follow advisories issued last year for Lake Monona is problematic for many reasons. Firstly, the Lake Monona PFAS advisories do not protect everyone–they include no special advice for vulnerable groups (women of child-bearing age, infants, children, etc.–over half the population). Toxicologists in New Jersey have advised that vulnerable groups eat NO fish with over 17 ppb.

Further, though not ill-intended, the DNR’s advice reflects a privileged cultural perspective. As MEJO has been saying over and over again for over 15 years, many anglers–especially low income subsistence anglers, largely people of color–are not aware of PFAS and other fish contaminants and the health risks they pose. They are much less likely to know about fish advisories than more privileged people, for a number of reasons. Many are not reading local newspapers. Why would they even think to look at the DNR website to find out what the advisories say? If they did, how would they even know where to look?

For many subsistence anglers of color, fish and fishing are culturally important and fish are critical food sources, especially now in these hard economic times. Many do not have the same food choices more privileged people have. Can they choose not to eat the fish and just buy fish at the store instead? Maybe, maybe not.

Will DNR and/or other government agencies do anything to meaningfully communicate and engage with these at-risk anglers–or to provide them with safer, contaminant-free fish? It doesn’t seem likely. They haven’t done much for decades here–and what they have done has been the result of our ongoing, challenging activism. We’ve learned that low income anglers of color are invisible to the powers-that-be in Madison.

EXTRA NOTES on sediments and PFBA

*What about creek and lake sediments?

PFAS levels in creek and lake sediments, especially the longer-chain compounds like the highly toxic PFOS, are likely very high. PFAS in these sediments will continue to leach into the water forever unless something is done to clean them up. For a number of reasons, there is huge resistance to testing them.

After repeatedly asking city, county, and state agencies to test the sediments, to no avail, MEJO and our East Madison Community Center Starkweather project team raised money and did the testing ourselves. Of course, we found significant levels of PFAS—up to27,800 ppt total PFAS–-just downstream of the airport and Air National Guard base.

Our sediment findings were reported in the Cap Times and Northside News, but city and county officials dismissed (or ignored) them. The teens who participated in the project, most of whom live in the Truax apartments, have also been ignored. Health risks to the low income people living at ground zero next to the heavily PFAS-contaminated Starkweather Creek (Truax public housing, Darbo Worthington apartments) are clearly very low priorities for the powers-that-be.

Our sediment findings were reported in the Cap Times and Northside News, but city and county officials dismissed (or ignored) them. The teens who participated in the project, most of whom live in the Truax apartments, have also been ignored. Health risks to the low income people living at ground zero next to the heavily PFAS-contaminated Starkweather Creek (Truax public housing, Darbo Worthington apartments) are clearly very low priorities for the powers-that-be.

**The PFAS compounds PFBA was found in all the lakes at significant levels

Should we be concerned? Where did the PFBA come from? Does it pose health risks to anyone?

According to the Minnesota Pollution Control Agency, PFBA “is commonly used in non-stick and stain-resistant consumer products, food packaging, fire-fighting foam, and industrial processes. PFBA is a breakdown product of other PFCs used in stain-resistant fabrics, paper food packaging, and carpets. PFBA was also used for manufacturing photographic film. The 3M Company was once a major manufacturer of PFBA.”

Fortunately, so far evidence indicates that PFBA doesn’t build up in fish as much as longer-chain compounds. Does that mean we shouldn’t worry about it because nobody is exposed? No. PFBA is extremely mobile–it spread over a 130 mile radius from the 3M PFAS-contaminated sites in Minnesota (see slide 16). It is common in landfill leachates–and old landfills are all over Madison, leaching contaminants slowly into the lakes.

Also, because PFBA is smaller, it is more volatile, so it can spread more readily via air, and that may be why it is in all the lakes–even Mendota, which is not downstream from Truax Field. Is it volatilizing off the lakes? Perhaps.

PFBA is also found at significant levels in some Madison municipal wells southeast of the Truax base, such as Well 9 off Buckeye Road. Does this PFBA indicate the leading edge of the Truax plume, which the Minnesota 3M studies indicate it might?

The Water Utility assures us that these PFBA levels are nothing to worry about, because they are well below the few drinking water standards out there for this compound.

Should we be comforted by this? No. Unfortunately, the Madison Water Utility is not paying attention to the most up-to-date science.

Industry and PFAS risk “downplayers” have been assuring us for years that smaller-chain PFAS are less toxic. But the argument that PFBA is less toxic than longer-chain compounds is not holding up as more scientific studies are done. In time, as further studies are done, the levels considered “safe”–and the standards–will go down, as happened with other kinds of PFAS, such as PFOS and PFOA.

Also, standards are heavily influenced by polluters and chemical manufacturers. Manufacturers of PFBA, like powerful 3M, are likely lobbying to keep standards for this compound as high (unprotective) as possible so that they won’t have to clean up all the PFBA they manufactured and that is now everywhere.

This is a well-worn regulatory evasion game known as chemical “whack-a-mole.” Chemical manufacturers switch to slightly different variations of chemicals as certain types are regulated. PFAS manufacturers have played this game very effectively.

As described in a recent paper in Environmental Science & Technology, when they phased out the longer-chain compounds (far too late), due to public and governmental pressure, major manufacturers switched to less-studied (or unstudied) smaller-chain compounds, which they called “safer alternatives.” The authors elaborate on why this isn’t true (references are removed):

“Research has demonstrated that short-chain PFAS can be equally environmentally persistent and are even more mobile in the environment and more difficult to remove from drinking water than long-chain PFAS. Bioaccumulation of some short-chain PFAS occurs in humans and animals, and research in fish suggests they can do so in excess of the long-chain compounds they aimed to replace. Short-chain PFAS also can be more effectively taken up by plants. Because short-chain PFAS have, to a large extent, replaced the long-chain PFAS in commerce, the levels of short chain PFAS, such as perfluorobutanoic acid (PFBA), perfluorobutanesulfonic acid (PFBS), and perfluorohexanoic acid (PFHxA), have increased in environmental media. To date, relatively little is known about possible health effects of long-term exposure to short-chain PFAS. However, a growing body of evidence suggests they are associated with similar adverse toxicological effects as long-chain PFAS.”

This is one reason among many (as described in the ES&T paper linked above) we need a “class-based” or “summed-total” approach to assessing and regulating PFAS compounds. There are thousands of PFAS compounds on the market, so many of us are eating, drinking, and breathing hundreds if not thousands of PFAS compounds at a time. Testing and regulating one PFAS compound at a time does not protect public or environmental health. It also benefits the producers of PFAS, who can just keep playing “whack-a-mole” game forever. ”